by Kayhan Mashouf, DDS

Clear aligners in orthodontics are no longer a recent technology. In fact, clear aligners have been in popular use for about 25 years, with Invisalign being the first company to have its aligners FDA approved in 1998. Since the expiration of Invisalign’s original patents in 2017, other companies have started to create their own clear aligners, and there is currently a plethora of clear aligner systems on the market. Which product a practitioner chooses to use is a matter of preference, however, there are certain advantages and disadvantages inherent to this treatment modality. This article will present the pros and cons of clear aligner treatment and how the cons can be navigated to produce desired orthodontic outcomes for patients with various conditions.

Since they cover the occlusal surfaces, one benefit of clear aligners is their ability to “push on” or intrude teeth, and with the help of strong occlusal forces aligners are particularly effective at intruding posterior teeth. For this reason, clear aligner treatment can be a great option for correcting anterior open bites because these often present as situations where the posterior teeth are over-erupted relative to the anterior teeth.

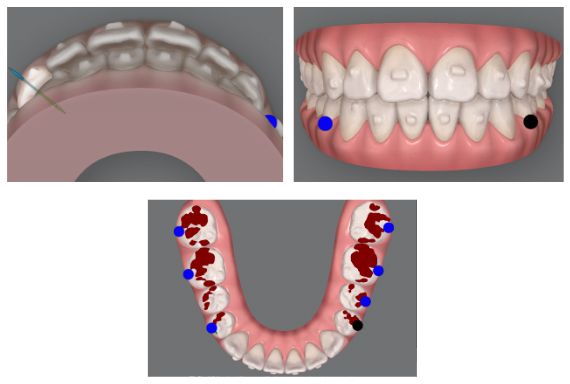

For the patient below with a mild-moderate anterior open bite, notice how the premolars and molars are on different planes compared to the incisors. Lines have been drawn in the upper arch to show this although the same is true for the lower arch.

After 9 months of clear aligner treatment involving intrusion of the posterior teeth and extrusion of anterior teeth, the open bite was closed. In the posttreatment photos below, it is now apparent that the lines representing the posterior and anterior planes more closely coincide with each other.

As mentioned, it was not only posterior intrusion that contributed to the closure of the open bite, but anterior extrusion as well. Extruding teeth with clear aligners is a more difficult movement to achieve, since the removable nature of aligners (unlike braces that are fixed to the teeth) makes it more difficult to accomplish “grabbing and pulling” movements. Nonetheless, extrusion is possible with clear aligners and bonding attachments to the teeth to be extruded makes this movement more likely to occur.

Worth mentioning is that the most common unwanted side effect that occurs with clear aligners also relates to their ability to intrude teeth, and that is the development of posterior open bite. The thickness of the aligners takes up space between the upper and lower occlusal surfaces when they are being worn, and even if intrusion of the posterior teeth is not intended it can still occur due this “wedging effect” of the aligners between the teeth. The fact that patients often clench or grind their teeth while the aligners are being worn only serves to increase the chances of an iatrogenic posterior open bite occurring during treatment.

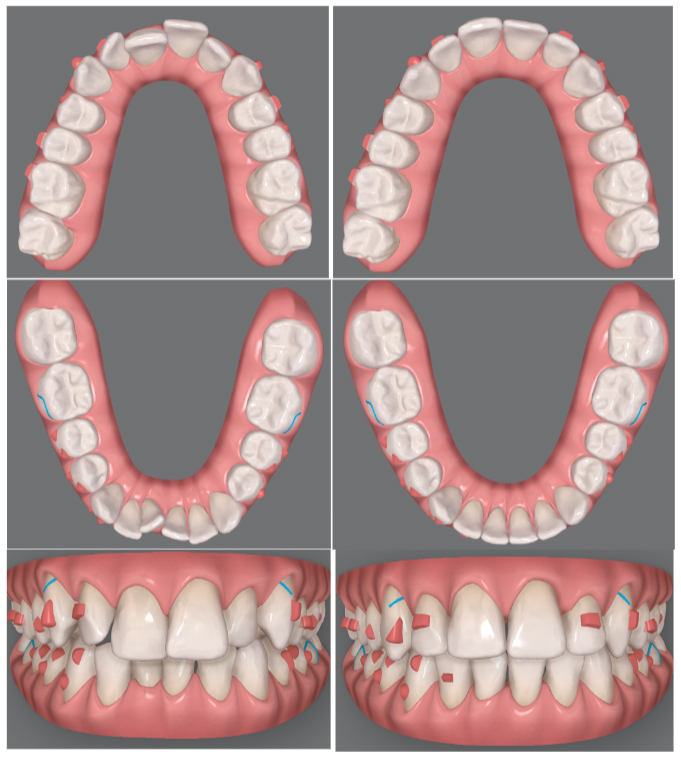

The case below is that of a patient who underwent clear aligner treatment with the goal of straightening his teeth. Note that he had a tendency for posterior open bite on the right side even prior to starting treatment as well as a slightly deep overbite.

Fourteen months into treatment his teeth were aligned but he had also developed a full-blown posterior open bite on the right side. I had made the mistake of not adequately extruding his posterior teeth on this side to counteract the wedging effect of the aligners, while also not accounting for his slight deep bite playing a contributory role and serving as an anterior stop to maintain the posterior open bite.

This problem created through treatment was troubleshooted by cutting out the right segment of the last upper and lower aligners distal to the 1st premolars (often these teeth are still in occlusion), bonding buttons to the 2nd premolars and molars, and having the patient wear vertical elastics between the upper and lower buttons during the day and night. About 2 months later the teeth had settled into occlusion. In instances where the posterior open bite is less obvious, cutting out the posterior aligner segment(s) alone might be sufficient for settling of the occlusion, and the use of buttons and elastics can be bypassed.

Measures can be taken to avoid creating an iatrogenic posterior open bite in the first place. During planning of a case, adding adequate buccal inclination to the upper incisors and intrusion to the upper/lower incisors will prevent the creation of premature anterior contacts. To reflect this when moving the teeth in the software, aim for an overjet that is slightly excessive and an overbite that is shallow (upper pictures below). Additionally, over-extrude the premolars and molars to help avoid unintended posterior intrusion. This will be reflected as hyper-occlusion of the posterior teeth in the simulated plan, which will not actually occur during treatment but will serve to keep the posterior occlusion closed (red marks, lower picture below).

Since their inception, clear aligners have been an effective option for closing spaces. They can even be considered a more predictable option for space closure than fixed appliances (braces), as the outcome can be planned on a computer prior to starting treatment. A broad array of spacing cases can be treated with aligners, but care should be taken to avoid one unwanted side effect– excessive tipping during diastema closure.

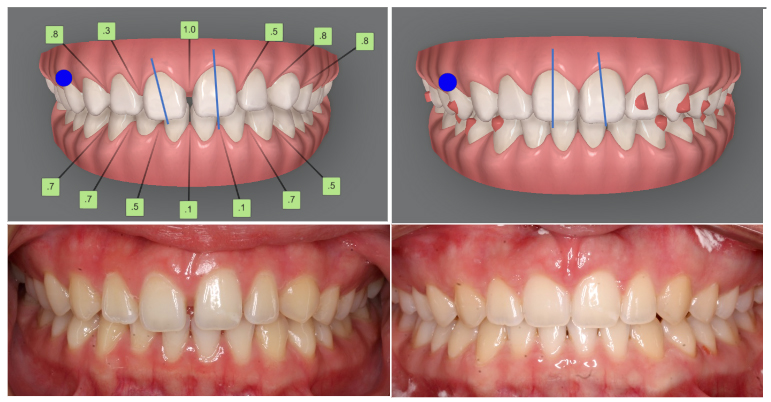

Below is an example of how this can occur in a patient who wanted to have the “gap” between her front teeth closed. The simulated treatment plan on the right side appears like it will close the midline diastema with the central incisors at ideal angulations.

What occurred clinically, however, was excessive tipping of the central incisors toward each other as the space closed (below). Correcting this side effect in a refinement stage is neither predictable nor efficient as aligners have difficulty moving roots, and in this instance the roots of the central incisors would need to be converged while distally tipping the crowns.

The options of clear aligner refinement or a short stint of braces were given to the patient but having lived with a large space between the front teeth for much of her life, she was simply happy to have it closed and did not want to continue treatment. In retrospect, a better outcome could have been achieved had I kept the crowns of the central incisors divergent in the treatment simulation when planning the tooth movements.

The following moderate spacing case is one in which the possibility of mesial tipping during midline diastema closure was accounted for. Observe the difference between the mesiodistal angulations of the central incisors in the first and last stages of the treatment simulation (lines drawn, upper left/right). The difference is subtle, but the central incisors are tipped more distally in the last stage compared to the first to compensate for their tendency to tip mesially during space closure. Subsequently, the comparison of pretreatment and posttreatment clinical photos shows that the central incisors were able to a maintain normal angulations during treatment without tipping too mesially (lower left/right).

Treatment of spacing has always been a strength of clear aligners, but the same has not always been true for crowding. In the early days of aligner technology, attempting to correct moderate to severe crowding would often lead to issues with poor tracking of the aligners due to their inability to effectively “grab” the teeth undergoing extensive rotational or tipping movements. This changed with the introduction of bonded attachments, which not only provide more surface area for the aligners to grab onto, but can also be varied in shape, size, and position to accomplish complex movements.

While clear aligners have evolved into a viable treatment option for crowding, aligning teeth that are excessively tipped and/or rotated can be a challenge. The patient below presented with moderate upper/lower and wanted to improve her smile. Notice her teeth were misaligned in a variety of ways, i.e., buccolingual discrepancies, mesiodistal tipping, and rotations.

After undergoing 10 months of aligner treatment her teeth were mostly aligned (below). Remnants of the crowding could still be observed, however, at the slightly rotated upper laterals, slightly lingual upper right central, and the rotated lower right central. Already burnt out from wearing the aligners, she opted not to pursue further refinement.

The pictures below show the initial (left) and final (right) of the tooth movement plans for this patient. Looking back, I could have bonded attachments to the upper and lower central incisors for maximum control of their movements. Additionally, the movements of the most misaligned teeth could have been exaggerated. I should have added more overcorrection to the upper lateral incisors and lower right central incisor rotations, as well as to the labial movement of the upper right central incisor. Lastly, I should have overcorrected the mesial crown tip of the upper right lateral, with its final position tipped distally rather than parallel with the adjacent teeth.

The benefits of clear aligners for treatment of anterior open bite, spacing, and crowding have been presented. Common pitfalls of aligners, namely creating unwanted posterior open bites, excessively tipping teeth during space closure, or failing to fully align severely rotated or tipped teeth were identified, along with strategies for preventing or troubleshooting these situations. There is much that can be covered regarding the strengths and weaknesses of clear aligner therapy, too much for one article, but hopefully readers come away with an improved sense for case selection and management of clear aligner treatments within the scope of what has been discussed.

Questions for the author can be emailed to klm@drmashouf.com.